The story of the rise of the Zsolnays from Pécs in Hungary has strong parallels with the life of the family of the somewhat younger Emile Gallé (1846-1904) in Lorraine. Like Gallé, Vilmos was the son of a wealthy merchant. Like Charles Gallé, his father Miklós Zsolnay (1800-1880) was given the opportunity to buy up the inventory of a local earthenware factory. His older brother Ignác (1826-1900) managed the newly established factory from 1854-65.

The career of Vilmos (1828-1900), who was interested in art and science – another parallel to the Lorraine artist – initially followed in his father’s footsteps. He studied business administration at the Polytechnic in Vienna and completed an apprenticeship in a gallantry shop. In 1853, back in Pécs, he succeeded in transforming his father’s business into a modern department store, modelled on the Parisian department stores that had recently opened their doors. Even in the early years, he established contacts in other western countries. This was to give him an advantage in later years. Vilmos had the foresight to invest with great success in sectors outside the industry, such as railway construction, coal production and the timber industry.

Initially, the earthenware factory was not under a favourable star. The Hungarian Revolution and the secession from the Habsburg Empire in 1848/49 had led to a period of economic difficulties. A lack of subsidies and high customs duties affected both production and sales of traditional tableware and technical objects. For eleven years, the company struggled to keep its head above water until Vilmos was able to pay off his brother’s debts by taking over the factory in 1865. The younger brother threw himself into the new task full of vigour and continued his education in the artistic field. His collection of ceramic samples from all over the world and from various centuries was extensive. Materials, glazes, techniques – nothing was beyond his thirst for knowledge. The factory’s everyday crockery was gradually supplemented with luxury items.

When choosing new employees, Zsolnay relied both on long-established, traditional ceramists who worked in the typical Hungarian style and on specialists from the other ceramic – mostly German-speaking – centres of Western Europe. He also attached a school to the factory in order to train young talents himself and retain them in the factory. His own family was also involved in the business. His daughters Teréz (1854-1944) and Júlia (1856-1950) were initially sent on trips around the world to gather inspiration for decorations on textiles and ceramics for the factory. While Teréz was mainly occupied with collecting, cataloguing and preserving the pieces after her return, Júlia worked quite naturally as a designer in the factory. It was also Júlia who developed the factory’s five-spires signet, which is still recognised all over the world today.

The youngest, his son Miklós (1857-1922) took over the commercial side of the business in 1878, while his father continued to look after the artistic side of the factory himself.

Further worlds opened up for Zsolnay at the world exhibitions in Vienna in 1873 and Paris in 1878. Inspired by the ancient Chinese and Middle Eastern ceramics, some of which were presented in their original form and some through the reception by ceramists from other European countries, he began, after his return, to work intensively in tandem with the chemist Vince Wartha (1844-1914) and developed new materials and glazes.

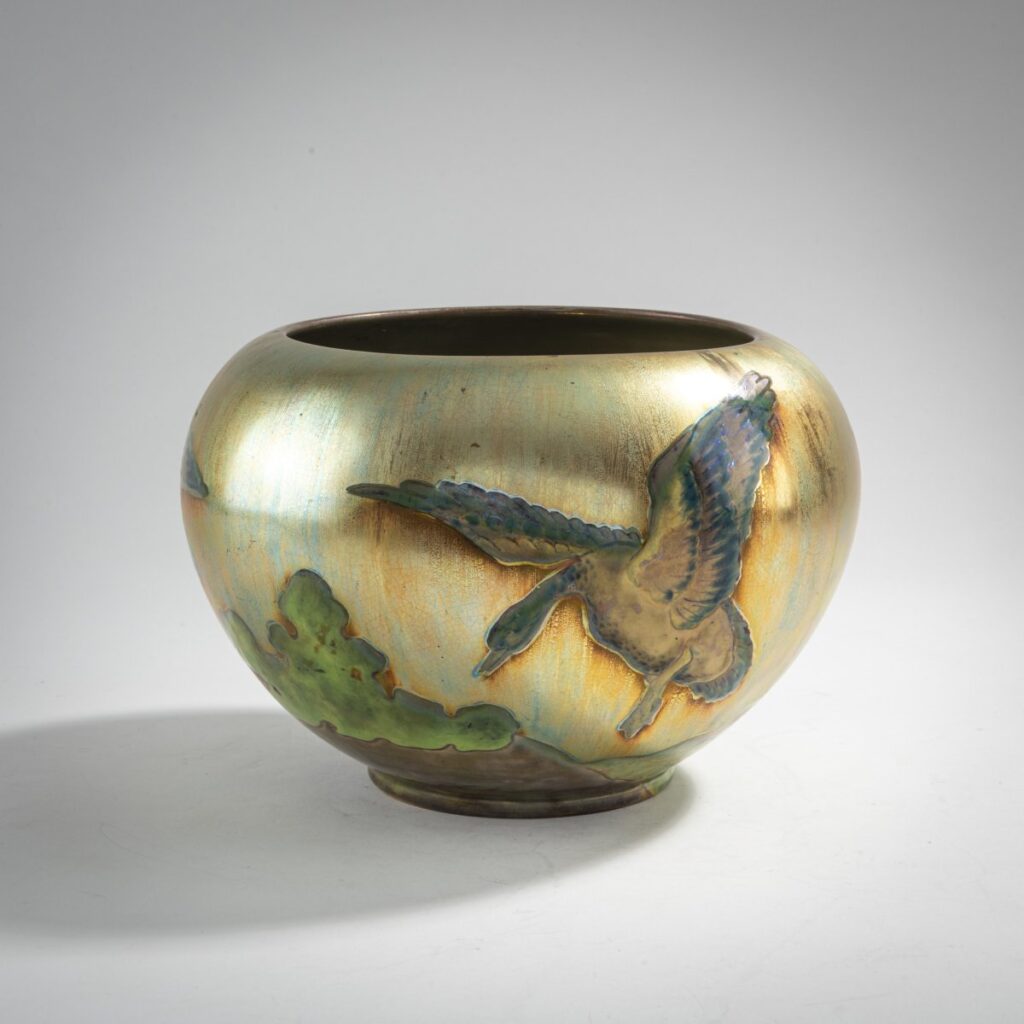

High-firing glazing was the first to find its way into the Hungarian factory. It was used on the newly developed porcelain faience, while Júlia was influenced by Persian models in her glazed designs. In 1887/88, Vilmos himself travelled to the Middle East. In the Egyptian city of Fustat, the centre of ceramics production in the tenth and eleventh centuries, he discovered the technique for which the Vilmos Zsolnay company is still world-famous today: the Eosin glaze. After numerous experiments, he recorded the recipe for the shimmering metallic glazing technique, which imitated antique glass, in his recipe book in 1891. The first eosin ware was presented with great success at the Hungarian Millennium Exhibition in Budapest in 1896. Among the customers for his new, Art Nouveau-influenced luxury goods were artists and statesmen from all over Europe, members of the Hungarian aristocracy and even Emperor Franz Josef himself is said to have paid a visit to the factory in Pécs.

After Vilmos’ death in 1900, the factory was run by Miklós and the two daughters, then by his grandsons Tibor, Zsolt and Milos. After the First World War, the factory gradually lost importance, albeit the manufacture never stopped. After the Second World War, in 1948, the Zsolnay family was expropriated and the factory passed into state hands. It was not until 1974 that production resumed under the Zsolnay name.

Since 2011, a cultural quarter is standing on the former site of the factory in Pécs, the European Capital of Culture. A museum, galleries, the reconstructed mausoleum of Vilmos Zsolnay and a beautiful park with numerous restaurants are open to visitors.

Even today, collectors still enjoy the factory’s beautiful works. In recent years, we at Quittenbaum have been able to sell several exceptional vases and bowls with great success.

A cachepot with enameled wild duck decoration rose from EUR 1,200 to EUR 5,000 in 2024. Shortly before, a tall vase with a sinuous semi-plastic dragon, circa 1901, had been hotly contested. The vase with a shimmering dark blue and gold Eosing glaze was only knocked down for a proud EUR 54,000 after a battle lasting several minutes at an asking price of EUR 4,000.

https://www.zsolnay.hu/pages/the-zsolnay-family

https://trespasser-on-earth.org/hungary/zsolnay/

https://www.zsolnaynegyed.hu/de/informationen/uber-das-kulturviertel-zsolnay